Achieving More With Less Using Token Compression

Blaise Pascal, is quoted to have once said "if I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter”. Beyond the disputes over free will in which this quote appeared, it highlights the difficulty of achieving the same meaning with fewer words. Something most of us are familiar with.

Today’s LLMs are no different. As users pay per token, long prompts are costly, they also cost attention and impact memory by increasingly cluttering the context window, making accuracy decay, hallucinated references appear and constraints disappear.

While the choice of natural language as a universal UI has proved to be efficient, there is an anthropomorphic side to using it the regular way. Language evolved more to suit humans than machines, and machines don’t always require the precision and formatting humans need. This opens up different perspectives on reducing the number of tokens a prompt contains, reducing as a problem of keeping the tokens that trigger the best response of an LLM. Token Compression is a field that explores this, with some bridges to information theory.

In the following we’re going to explore an overview of some of the fundamental techniques used in it.

But first, let’s clarify some concepts.

What is compression and what to compress ?

Prompt compression is the process of reducing the size of a prompt while preserving its intended behavior and task performance. This behavior can be made explicit through proxies like :

- Hard constraints

- Required outputs

- Alignment

- Accuracy

A prompt can be viewed at different levels of granularity. A collection of characters, words, tokens or vectors. This impacts the way one goes about compression.

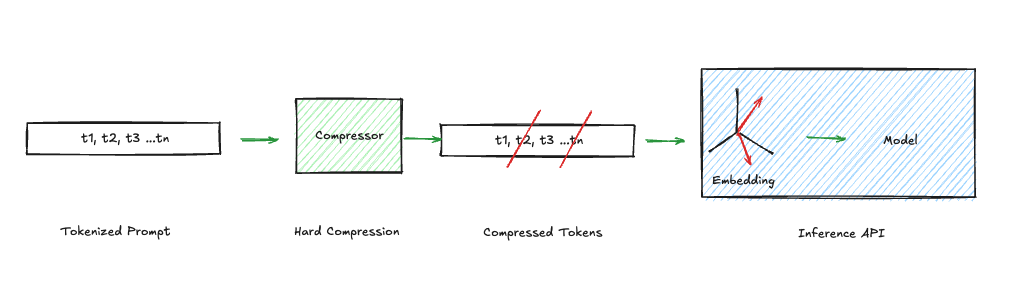

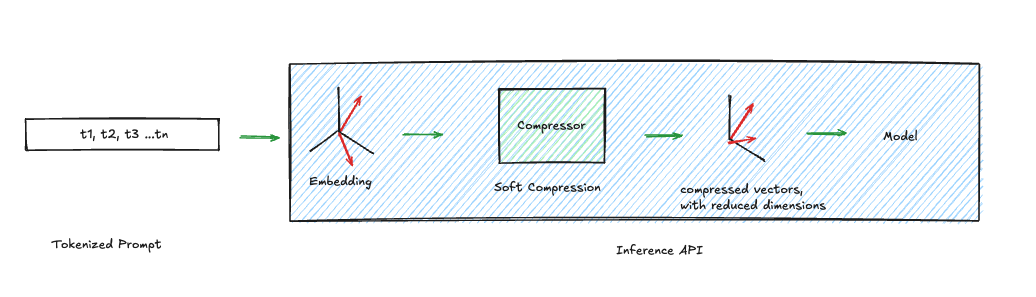

From the architectural point of view we distinguish two places to compress a prompt: before the model sees it (token-level), or after it has been represented (embedding-level).

Token-level compression - Hard Compression

This shortens the input sequence. It operates in discrete symbol space, where one can rewrite, deduplicate, or summarize the text so fewer vocabulary tokens enter the transformer. This gives immediate wins: less context usage and lower attention cost (quadratic in sequence length). Also, the embeddings the model receives are still exact rows of the embedding matrix—each input vector corresponds to a real token ID. This makes token compression transparent and debuggable: one can inspect precisely what constraints remain. But it is brittle. If a sentence containing a negation, a numeric bound, or an exception clause, is deleted, that constraint disappears entirely. The failure mode is discrete and catastrophic: the rule is simply gone.

Embedding-level compression - Soft Compression

This operates in continuous space. Instead of reducing the number of vocabulary tokens directly, one can reduce or replace their representations. The original token embeddings are projected or pooled into a smaller set of dense vectors . These vectors are often mixtures of many token embeddings. Crucially, they do not need to correspond to any actual vocabulary entry; they are valid points in embedding space but not valid discrete tokens. This is why they are sometimes called “soft tokens”: they are continuous vectors not tied to a specific symbol in the vocabulary. Because the mapping is many-to-one and lower-rank, fine-grained distinctions can blur. Negations, rare entities, and exception clauses often occupy low-variance directions in embedding space; projection can compress those directions away even if overall semantic similarity is preserved. The result is smooth degradation rather than hard deletion: the model retains the gist but may lose exact symbolic fidelity.

In short, token-level compression reduces sequence length and preserves discrete structure, while embedding-level compression reduces representational dimensionality and preserves approximate meaning. The former risks dropping constraints entirely; the latter risks blending them into something semantically similar but logically softer. Applying one or the other depends on the intended behavior, but can also depend on the setting in which the inference is taking place, as well as what information is at disposal.

The case of Black-box LLM models

In most use cases, people don’t have access to the model weights or even to other parts, like the architecture and the embeddings. This makes Embedding-Level Compression hard to get and therefore Token-level Compression the more appropriate technique for this case. Moreover, compressing at the token level allows a more flexible usage of several models in a plug-and-play fashion, since the compression process is independent of the inference. This is especially the case for gateways for example.

Having established this, several categories of token-level compression exist, following the techniques and types of transformation that they apply on the tokens. In the following, we try to investigate the fundamental ones.

Filtering

In the broad sense, it consists in removing tokens that don’t add meaning to the prompt or that are deemed generic. It includes:

- Stemming, which reduces words to a crude root form by chopping off suffixes. For example, “designing” → “design”

- Lemmatization, it reduces words to their dictionary base form but in a much semantic way. For example: “better” → “good”

- Stop words removal, that operates simply by removing some prepositions that operate as syntactic glue. For example: “the”, “a”, “an”.

Most of these techniques are a legacy of Natural Language Processing. And although they have the advantage of being highly debuggable, creating an easy feedback loop, they still operate on a surface level. They are not aware of meaning and therefore can remove things that are crucial to perform the task, like removing a simple negation prepositions that could invert the prompt constraints.

For this, another family of filtering techniques tries to upgrade, by working on a semantic level. Dedupe Clustering is one of these.

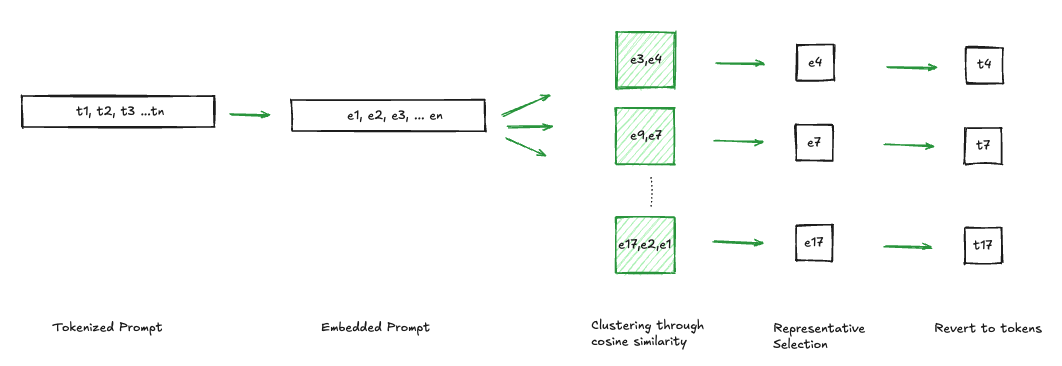

Dedupe Clustering

The gist of this technique is to filter parts of a prompt that contain the same semantic information. For example, “Do not be verbose” and “Keep your answer short”.

The idea is to split the prompt into chunks, these can be words, sentences, bullet points or any other markers. The granularity depends on the use case. Once the splitting done, each chunk is embedded as a vector. The result is a set of vectors that can be grouped into clusters according to a metric. The most used is a cosine similarity. Therefore all the vectors that are within a certain pre-defined threshold of each other end up in the same cluster and one can for a certain cluster keep one or more representatives. The rest could be considered as carrying the same meaning.

This offers the backbone to several other techniques as well as different degrees of control, like the threshold, the similarity metric or the number of cluster representatives to consider.

Paraphrasing

This is the good old summarization technique. It involves re-writing the prompt in a shorter way. The most common way is to use another LLM with a lower cost, either by instructing it to output a shorter version or by training a summarizer for this purpose. The simplicity of this technique comes at the cost of not having that many degrees of control and adjustment as these are, once the training phase done, handed over to the summarization model.

Selective Retrieval

This is not a proper compression technique per se, in the sense that it does not reduce the size of a given prompt. It rather makes the context around that prompt fit in a certain context-window. The most used ones are Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), the use of vector databases and the use of tools like grep. These operate by selecting only parts of the context that are relevant to the prompt. The criteria for selection can be semantic (like cosine similarity) or syntactic (like regex).

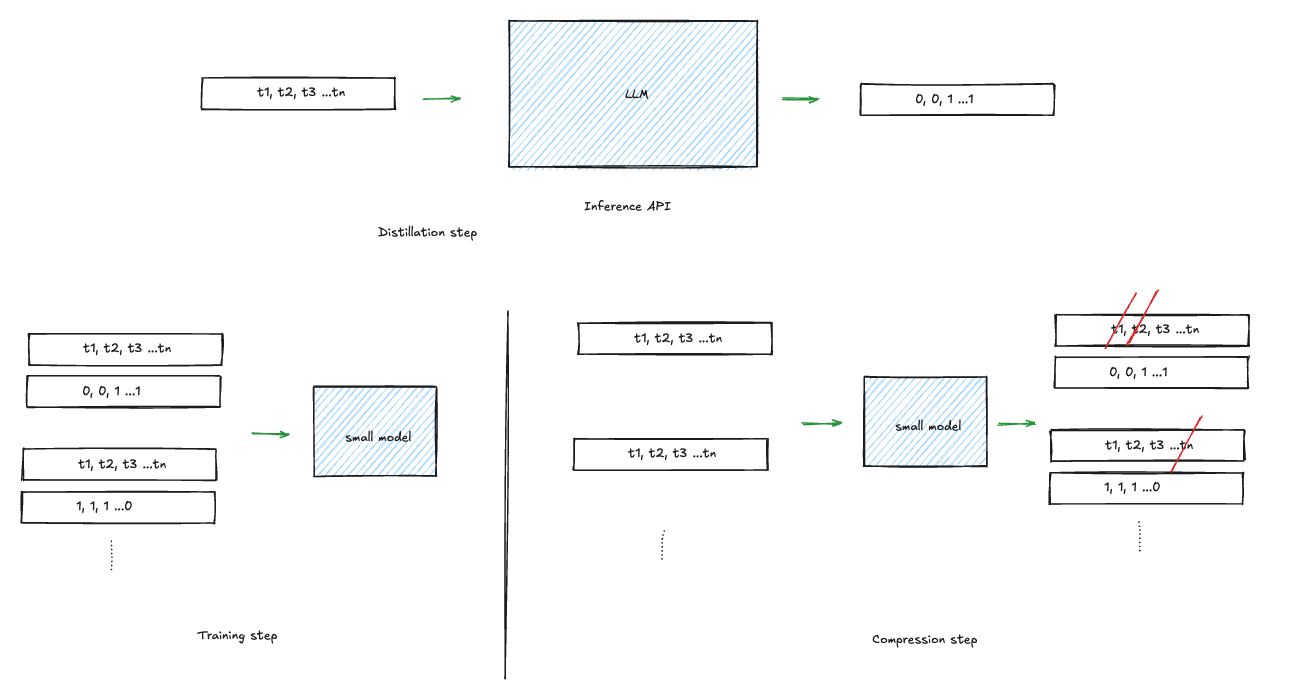

Distillation

The insight in distillation based compression is that only the model knows what tokens are important or not to achieve a certain task. The idea is then to extract this knowledge into a smaller model. This works by collecting a sample of prompts, instructing the big model to compress it by removing non necessary tokens. We can then take the original prompt and label its tokens according to the result by writing 0 to each removed token and 1 to the ones the model kept. Doing this over a large dataset gives a training set for the smaller model.

To have more control over the compression, one can instead of instructing the model to reduce the prompt by removing tokens, output a scoring of the tokens following their importance in the prompt. This labeled dataset can once more serve to train the small model to output a score for token importance within the prompt.

All these techniques can be task-agnostic or task-dependent according the dataset that the models / embeddings are trained on. One important issue is how to measure the impact of the compression on the performance of the desired task

How to measure the impact of compression ?

In its purest form, compression is a transformation of the input prompt. This transformation can have impact on several behaviors that the user can see:

- Latency, as the transformation adds computational cost on top of the inference, some milliseconds can be expected to prolong the time to first token

- Cost, hopefully, a functioning compression reduces the number of tokens sent to the model and therefore the cost.

- Performance, as the input is a transformed version of what the user gives, he/she would expect no change in behavior of the task performed or the output response

The user can operate on latency by adjusting the computational cost of the compression technique. Using a lighter approach, consumes less time and has less impact on latency. Other architectural solutions, like doing the compression at edge helps reducing it.

On the other hand, cost is just inversely proportional to the number of saved tokens. Despite the differences in tokenization algorithms that would affect the count and the differences from run to run, a compression ratio of the number of the tokens in the compressed prompt over the ones in the original gives a pretty straight forward idea on the impact.

Performance on the other hand, is harder to quantify. The non-deterministic behavior in LLMs make it also difficult to run A/B test styles of comparisons to measure the impact before and after compression. We usually fallback to proxy metrics like:

- Human evaluation, by just letting the user observe the drift in behavior over a large sample or tries. As this can be done at use time, it can encounter scalability problems

- LLM as a judge, delegating the measure to an LLM that can say if the compressed prompt does not alter too much the input prompt or the response

- Proxy metrics that try to capture semantic preservation of the compressed prompt. Among these we can count semantic cosine similarity, ROUGE or BertScore.

All these measures are in interplay when taking a decision about compression. Often they guide decisions like when should we compress ? How much compression is too much ? and what trade-off philosophy should guide us?

In the next parts of this series we’ll explore such questions, as well as other techniques and the empirical decisions surrounding them.

Conclusion

Token compression is not merely an optimization trick; it is a structural design decision in the age of large language models. As context windows expand and pricing remains token-bound, the incentive to compress grows. Yet compression is never neutral. It is a transformation of intent.

At the token level, compression forces explicit trade-offs: remove too much, and constraints disappear. At the embedding level, compression softens distinctions, risking semantic drift rather than outright deletion. Each technique operates along a different axis of the precision–efficiency spectrum.

The real challenge is not reducing tokens, but preserving behavior. Compression should therefore be evaluated not only by how much shorter a prompt becomes, but by how faithfully it maintains alignment, constraints, and task accuracy.

In this sense, token compression becomes an information-theoretic problem: how much structure is necessary to reliably trigger a desired response? As LLM systems become more complex—multi-model pipelines, retrieval layers, edge deployment—the ability to intentionally shape and compress prompts may evolve from an optimization technique into a core competency of AI system design.

Writing shorter prompts, like Pascal’s shorter letter, is not simply about saving words. It is about understanding which words truly matter.

If I had more time I would have written a shorter blog.